IEEC marks the beginning of the academic year for many enterprise educators and this year’s conference, hosted by Glasgow Caledonian University and organised by EEUK and NCEE, was a great start. My highlight (of this, and perhaps every IEEC so far), was the session from Babson College’s Heidi Neck. From enthralling the conference with a bar trick, to opening the door on her entrepreneurial classroom, and concluding with a serious point about the need for a scholarship of teaching and learning in entrepreneurship, she was warm, wise, entertaining. She packed the conference hall (on Friday morning, the last day of a three-day conference, the night after a Glasgow Ceilidh). So, thank you Heidi for your energy and generosity, and congratulations IEEC 2017 hosts and organisers for that genius scheduling. There was much to love across the rest of the workshops, keynotes, and conversations over coffee. Here’s three thoughts that kept me occupied on the drive home

- The Emperor’s New Clothes

The first workshop I attended on Wednesday was a provocative session run by Young Enterprise Scotland where they challenged the audience to consider the extent to which ‘sales’ and ‘sales training’ were a part of enterprise education provision. Delegates reflected that in the start-up process, interacting with real humans (potential customers with whom you might actually talk in person or on the phone), is a difficult step for many students to make. Students might have an idea, they might even have completed a Business Model Canvas or started to make a plan, but the work of validating their ideas with potential customers is out of their comfort zone (initially, at least). I wondered to what extent this reticence may be supported by the ways in which they have previously come into contact with ‘enterprise.’ The Evaluation of Enterprise Education in England (Mclarty et al, 2010), identified that ‘enterprise challenges’ were the most frequent and favoured ways of delivering enterprise education to pupils (favoured by 90% of surveyed schools). Such activities are often characterised by groups of pupils spending a day, or half a day in the school hall, working in teams to respond to a challenge. Typically, the climax of such activities is pupils presenting their ideas and one team being judged the winner on the day. A side effect of such a format is to divorce the idea development process from the most crucial element of the reality of start-up – the customer. Steve Blank describes how ‘customer development’ is a key activity for founders – talking to potential customers in order to test, improve or change ideas. But the ‘compete and pitch’ format, structured as it is around a final ‘judgement’, might lead students who take part in such activities to believe that the idea alone, if it’s good enough, is going to be a winner. The Young Enterprise Scotland presenters asked – are we encouraging students to think more about ‘selling out’ than selling to customers? Have a look at the Kauffman Sketchbook video which describes how what they call the ‘plan and pitch’ narrative characterises less than 1% of start-up journeys in the US. The takeaway – the success of elite entrepreneurs might be an exciting and understandable format, but it is not a reflection of the reality of 99% of start-ups.

2. We need to talk about enterprise education

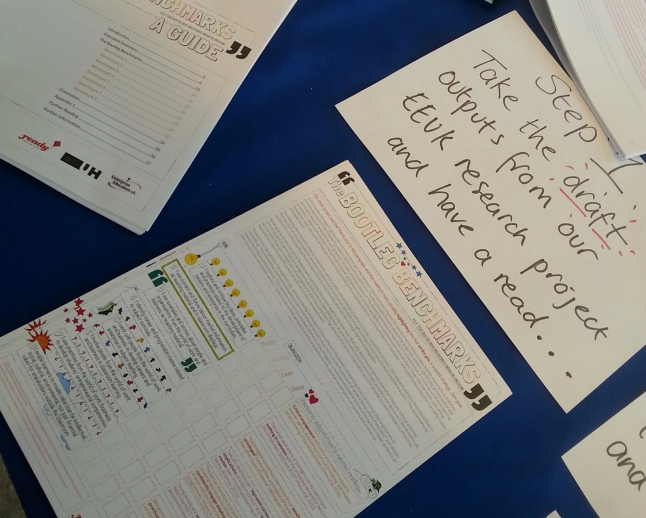

Offering an alternative to ‘compete and pitch’ was one of the aims of the EEUK research project which I and Professor Nigel Culkin from the University of Hertfordshire completed this year. We shared the results and draft outputs from our project – The Bootleg Benchmarks – which aims to underscore the role that teachers can play in the development of enterprise, and offer alternative ways for them to conceive and practice it (through the curriculum).

Some delegates I spoke to were aware of the national programme for careers and enterprise in secondary schools, special schools and colleges in England. It is underpinned by research by the Gatsby Foundation, which identifies eight ‘Gatsby Benchmarks’ –which schools can review and address to improve careers guidance in schools. In my work with schools, careers and enterprise coordinators have said they appreciate the practical approach of the Gatsby Benchmarks, and the focus on identifying pragmatic actions to support improvements. The Bootleg Benchmarks project aims to emulate that spirit – but at teacher level, rather than whole school.

Key policy and guidance were reviewed to clarify a picture of ‘what’s being asked of teachers?’, then related practices or actions were identified. Where there were potential gaps between the policy ambition (for example the aim for students to become more entrepreneurial), and the practice recommended (short term challenges and long-term enterprise competitions), research was undertaken to explain the potential pitfalls and alternative practices suggested. Our workshop sparked fascinating reactions, including:

- Reflections that the compete and pitch format was provided, accepted and replicated with little or no questioning of its underpinning assumptions or identification of aims and outcomes.

- Curiosity about why the ‘compete and pitch’ format is so prevalent.

- Comparisons between perverse effects of competitive approaches in enterprise education and those observed in fields such as sport, where research has shown that a focus on winning is not as effective as a focus on performance and process.

- Anecdotes about the pitfalls of competitions – winners who had an over-inflated sense of their simulated ideas, and losers who were discouraged by failure in a competitive process.

Of course, there were examples where people reported that competitions were useful and a relevant tool, for example identifying participants in business accelerators, or gaining publicity and prize money for teams and business development. The interesting question is whether a format which has a very specific purpose in the world of business (selecting a small number of entrepreneurs or a team for investment or reward), is a good model for developing the entrepreneurial skills, mindset and interest of children and young people. Perhaps this is where the role of teachers is crucial – they know their own students and are in a good position to decide for whom, and when, different interventions and pedagogies might be relevant and why. Heidi Neck’s keynote drove this point home; her conclusion: ‘The time is now’ for entrepreneurship scholarship to promote, value and reward a scholarship of entrepreneurial teaching and learning, not just research (thank you @dr_charlottew for capturing Professor Neck’s point!).

3. Realism can set you free

Which brings me to a final thought, related to the perennial issue of assessment and impact measurement, which came up in the Track Chairs’ takeaways and across a number of workshops and conversations. I appreciated the sentiment of Heidi’s liberating response to a question about the assessment of her course. She cautioned against over-obsessing with measurement, quoting Professor Jeffery Timmons advice to her: “Stepping on the scales won’t help you lose or gain weight.’ One of the problems is that in an age of constrained resources, short term projects and competition for funding, the pressure to prove impact and justify ones’ existence can feel irresistible. The ‘What works?’ agenda, and the limited methodological tools which support it (such as Randomised Control Trials and systematic review) contribute to this, by leading policy makers, commissioners and practitioners to conclude that it is interventions that ‘work’, and therefore our goal should be about identifying and scaling the most effective of those. Our research harnessed an alternative philosophy and methodology – utilising the principles of Realist Evaluation. This approach has been developed by health and medical evaluators who are dissatisfied with the incomplete knowledge generated by RCTs and systematic reviews. The underpinning principles of Realist Evaluation (as described by Pawson and Tilley here, and Pawson here, and utilised and developed by a community of researchers here), provide an alternative way of conceiving how we explore and analyse complex, socially contingent programmes. One of the assumptions of realist evaluation is that programmes will always have different effects, for different participants, in different circumstances. Such an assumption can set policy makers, commissioners, providers and practitioners free – it enables us to extend the ‘evidence based policy conversation’ beyond ‘What works?’ and towards ‘What works, for whom, in what circumstances and why?’ A practical example of this could be observed at the end of Mick Jackson’s passionate and impressive keynote about Wild Hearts and his programme Micro Tyco. The last question he took from delegates was ‘What would your one takeaway for us be?’ and he reflected on his experience at a recent competition where two teams, one of conscripts and one of volunteers, were having different experiences (his takeaway was: the volunteers were getting more out of it). Such honesty is both refreshing, and necessary, for the field to come to a more sophisticated understanding of how to best target interventions and limited resources. Our second paper identified potentially important contextual factors and mechanisms which may contribute to different outcomes patterns; whether or not you wanted to do the activity was one of these factors. The following were identified as potentially important contributing factors to different outcome patterns in competitive enterprise learning:

- Are you competitively inclined?

- Did you volunteer?

- If you lost, did someone help you co-construct a positive meaning from the experience?

- If you won, did someone help you to stay grounded?

- Are you well-resourced – personally in terms of your capabilities and confidence, institutionally in terms of the educators and/or mentors supporting you, socio-economically in terms of your relative position to your competitors?

Paying heed to such factors can help policy makers and programme providers refine the design, targeting, promotion of (and claims made for), competitive interventions. As well as explaining the potential pitfalls of assuming competitive approaches will always benefit pupils, the EEUK project assets help set out alternative ways for educators to conceive enterprise education. The Bootleg Benchmarks tool and accompanying guide re-frame enterprise, aiming to introduce ‘entrepreneurship as practice’ and ‘value creation’ into the consciousness and pedagogical tool kit of secondary school and college teachers who want to infuse enterprise into subject teaching. Apart from the potential risks related to compulsory ‘compete and pitch’ through the curriculum, there are rewards in developing alternative approaches: Martin Lackéus demonstrates that ‘school subject knowledge’ is supported by value creation pedagogy, offering a way to bridge unhelpful skills vs knowledge dualisms which curse enterprise education debate. I’ve been lucky enough to get a PhD scholarship to explore competition in enterprise education, so if you have any reactions or thoughts about the research, or, if you’ve got any ideas about (or want to get hold of a hard copy of) The Bootleg Benchmarks tool and guide, get in touch with me at catherine@readyunlimited.com

Thanks again IEEC. It was great to see Glasgow Caledonian pass the baton to Leeds Beckett University for the 2018 conference. The dates (Sept 5th to 7th 2018), are already in the diary.

Thank you Catherine for this very informative and thought-provoking reflection. Pleased to see your still in the enterprise education zone. Do we need a national strategy? Jane

LikeLike

Thanks Jane, good to hear from you :-). I think there needs to be more engagement with and critique of policy, more challenging re the assumptions which underpin the signature activities and pedagogies in enterprise education (and time to explore alternatives), and a more sophisticated conversation around ‘what works?’ (eg, ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why?’). Can that be the strategy? 😉

LikeLike

I think it can – the HE Level of consensus at the 3 QAA events (Cardiff, London and Glasgow) plus the one at IEEC was pretty clear with very few dissenting voices indeed. What really matters to me in terms of making it work is understanding the needs and simply put, understanding what it means to an educator / teacher who know how learning takes place!

As Elin pointed out at IEEC, the policy picture is moving from industrial push to educational push… and don’t forget that England is one of the very few countries left without a policy!!!

For anyone not familiar with it – here’s welsh schooling’s future – as seen in one of our Uni’s sessions (We are doing the teacher training now. Please note the 4 purposes 😉 : http://www.uwtsd.ac.uk/media/uwtsd-website/content-assets/documents/wcee/successful-futures.pdf

LikeLike

Hi Andy, thanks for your comment. Apologies for my belated response too: start-of-termism. Couldn’t agree more with your comment re ‘what really matters’ – that is, understanding what it means for the educator who has to put it into practice…..and who often has a raft of other pressures and priorities to which they must attend, and to which they must feel that enterprise/careers adds value to, rather than takes time away from. That thought takes me back to the framing of ent ed in England – extra curricular, competitive activity, often delivered for you, rather than there being a sense of ownership, scholarship and practice directed at harnessing enterprise to enhance learning, teaching, the curriculum. Remember the empathy map from my IEEC/ITT workshop? What are teachers hearing/seeing/saying/doing and thinking in this framing? Enterprise: ‘takes time away from proper curriculum’, it’s ‘done for me’, it’s ‘someone else’s job’.

LikeLike